Fraud and economic crime rates are at record highs in the fintech space. Last year, the payment fraud attack rate across fintech increased by 70%. In 2020, global card fraud losses surpassed $28 billion and that number is expected to climb to $49.32 billion by 2030.

Recently, PayPal lost nearly $50 billion in market cap after disclosing that 4.5 million fraudulent PayPal accounts had been created to take advantage of its “$10 per account created” incentive program. But this is not an issue that’s unique to PayPal.

Fraud is a challenge that all companies offering financial services need to learn to deal with. In this guide, we explore card program fraud in detail.

Founder TL;DR

- If you’re running a card program, fraud can meaningfully eat into your interchange revenue. A poorly managed program can have fraud losses north of 250 bps of total transacted volume. Even a well-managed program can lose around 50 bps.

- Fraud comes in many flavors. If you’re issuing cards, there are two main areas you need to worry about: onboarding fraud and transaction fraud.

- Onboarding fraud can include things like stolen identity, synthetic identity, and intentional abuse. Transaction fraud can include compromised cards, account takeovers (ATOs), carding attacks, merchant abuse, and friendly fraud.

- Fighting fraud is all about balancing top-line metrics (customer and transaction volume growth) with bottom-line metrics (profits and customer experience).

- Optimizing for top-line growth means more risks, which can lead to higher losses, more operational effort, and lower unit economics. Optimizing for bottom-line metrics usually means taking fewer risks, which helps you reduce losses and improve unit economics (at the cost of company growth).

- The best tool to help fintechs balance top-line and bottom-line goals is friction. If you’re issuing cards, you should consider how much friction you’d like to apply and where to apply it in order to create that Goldilocks “just-right” balance.

What is fraud?

Fraud refers to the use of intentional actions to generate unlawful gains from a target. It’s when a bad actor intentionally uses lies and deception to steal money (or some other store of value) from a company or individual. Notice the key word here is intent.

Under common law, three elements are required to prove fraud:

- A material false statement with an intent to deceive

- A victim’s reliance on the statement and damages

- Damages

Fraud is distinct from credit risk. Both result in a company ultimately not having the funds they deserve, but credit risk refers to a well-intentioned party’s inability to pay. Fraud instead involves an ill-intentioned party’s unwillingness to pay.

There is no such thing as an accidental fraud — intent is the only thing that separates error and credit risk from fraud.

Why does fraud matter to fintechs?

Fraud impacts a fintech’s bottom line and customer experience.

A poorly managed program commonly may have fraud losses north of 250 bps (or 2.5%) of total transacted volume. Even a well managed program may experience fraud losses around 50 bps. Fraud can meaningfully eat into interchange revenue, if not managed appropriately.

Ultimately, fraud impacts a company’s viability, both by drawing down its coffers and degrading the customer experience. As a result, it is important to be thinking about fraud early when building a card program.

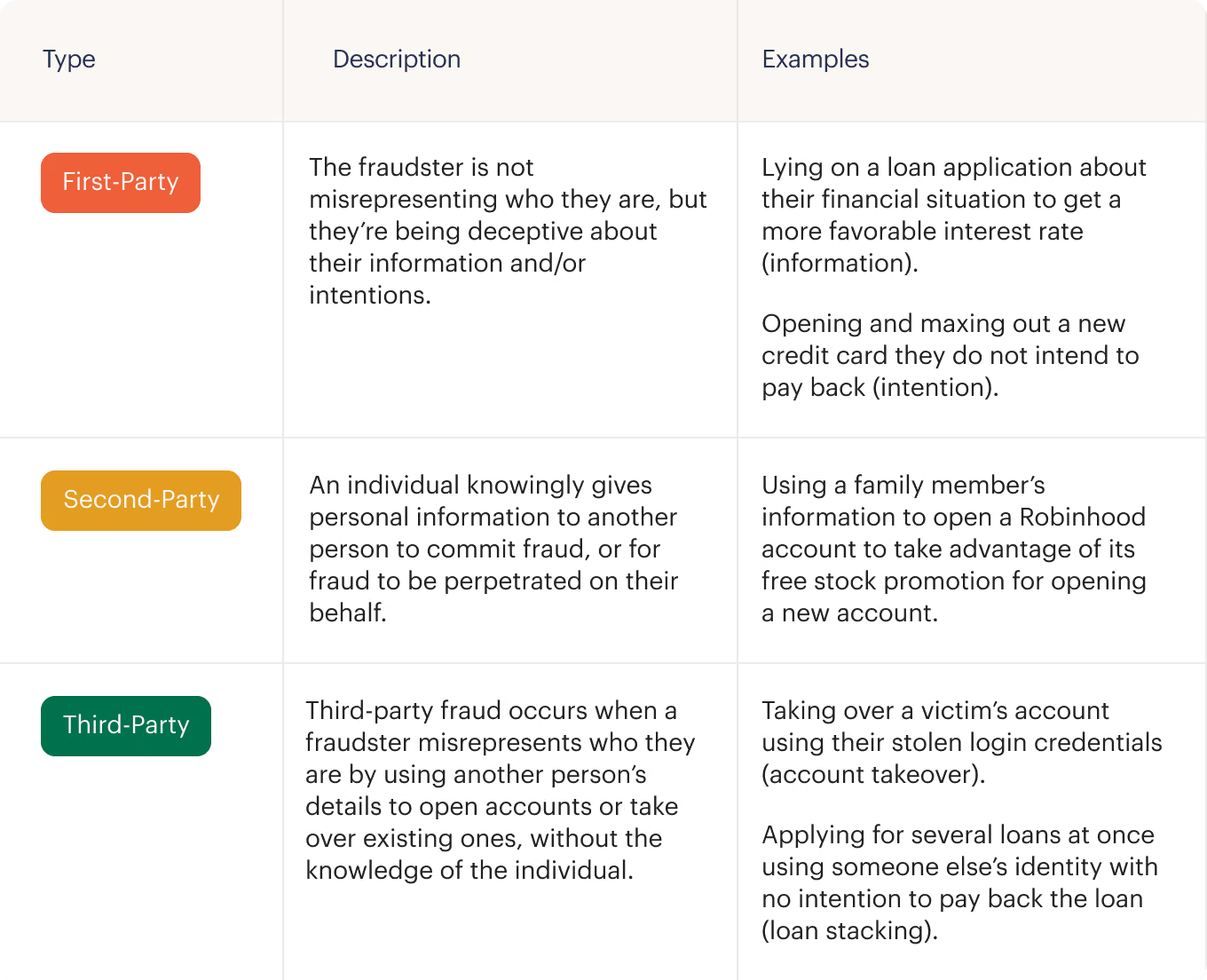

Three different types of fraud

There are generally three different types of fraud that fintechs commonly encounter.

In this blog, we break down the essentials of online payment security and fraud prevention.

Fraud across the customer journey

At Lithic, we like to think about fraud vectors across the customer journey, categorizing fraud between onboarding fraud risk and transaction fraud risk.

Onboarding fraud risk

When opening a new account, there is a variety of ways a bad actor might try to start a relationship with the intent to ultimately defraud the company.

Stolen Identity

- More than 33% of US citizens’ basic identity information has been exposed to bad actors. Fraudsters commit identity theft when they illicitly gain access to this personal information.

- For card programs, this means fraudsters can open a card in the name of a stolen identity.

- Most stolen identity cases are committed by bad actors who do not personally know the victim, but there are also cases where family members, friends, or colleagues of the victim are the ones stealing their identity.

Synthetic Identity

- When a bad actor uses fake identity elements (like a made-up name, address, date of birth, or SSN) to avoid detection, that is considered using a synthetic identity.

- It could be as simple as someone slightly amending their name and date of birth in order to get the benefits of an account opening promotion from a company they already have an account with.

- There are many cases where the bad actor spends months and sometimes even years building up the legitimacy of the fake identity they created.

- This can happen in real life (renting an apartment and paying utility bills under the fake identity’s name), in online records (manipulating credit bureaus so that the fake identity has a Consumer Credit Report), or both.

- For card programs: synthetic identities can be used by fraudsters to open accounts or get cards issued to themselves.

Intentional Abuse

- A criminal might use their own information, yet they have no intention to repay any loan or obligations they incur with the company.

- For card programs, this can mean initiating an ACH from an account that has enough money and draining the account of all funds after initiation.

- Similarly, long firm fraud is the act of obtaining goods or money on credit by falsely posing as an established business and having no intent to pay for the goods or repay the loan.

- Long firm fraud typically starts with criminals operating the business legitimately for a duration to establish a good credit history. Once having won some trust, the fraudsters then place several larger orders, promptly disappear, and sell the goods elsewhere.

- Short firm fraud is similar to long firm fraud but it takes place over a much shorter timescale. Usually, the business doesn’t try to establish any form of credit history or credibility, apart from perhaps filing entity formation documents or business registrations.

Transaction fraud risk

Once an account is open, criminals can defraud a company through a variety of means, including:

Card compromised

- This involves a legitimate customer’s card (also referred to as the PAN, personal account number) itself being compromised by a bad actor.

- In the physical world, this could include a card being stolen or a waiter ‘skimming’ the card number. In the digital world, this involves acquiring credit card information (e.g., from a data breach, on the dark web).

- While related to account takeover, this involves the card itself being compromised without the customer’s account credentials (i.e., username and password) being breached.

Account takeover (aka ATO)

- A bad actor gains access to a legitimate user’s account. With this access, they try to take funds from the account.

- Typically this is by transferring money to an account they control, using a card with a merchant they control (commonly referred to as self-pay), and/or buying goods or services for themselves (or to be resold).

- Account credentials or access can be obtained via dark web password reselling sites, or security exploits in a company’s user authentication, among other means.

Carding attack (aka PAN enumeration)

- A fraudster randomly guesses (enumerates) various possible combinations of numbers, trying to stumble upon a valid credit card number and CVV. Key to this scheme is a means to test if a random combination of numbers is a real card number.

- Typically, fraudsters use unwitting merchants who do zero-dollar authorizations, sometimes referred to as pre-authorizations, (say before a trial period on a subscription, or upon creating an account on an app store or marketplace). Once a valid card number is identified, the bad actor has effectively compromised the card.

Check out this blog to learn more about PAN enumeration attacks.

Merchant fraud

- This is a relatively broad category for anything nefarious that a merchant might do without the cardholder’s permission or knowledge.

- Manifestations can include scams (intentionally not providing the purchased products), double-charging (running the same transaction twice to make it appear like a technical glitch if caught), force posting (manually entering an authorization code to process a transaction), and unauthorized subscription (turning what was intended as a single purchase into a subscription without the buyer’s knowledge).

Friendly fraud chargebacks

- An actor makes a legitimate purchase, receiving the goods or services that they intended. Afterward, they dispute the charge claiming an issue (i.e., file a chargeback).

To learn more about friendly fraud, check out our Chargebacks Guide.

Fraud fighting basics

Fraud fighting strategies are usually centered around balancing top-line goals (customer growth and transaction volume growth) and bottom-line metrics (profits and customer experience).

- Companies wishing to take higher risks will see a boost in their customer growth and transaction volume, but that may translate to higher losses, higher operational efforts, worse unit economics, and degraded customer experience over time.

- A more conservative approach of taking low risks and applying more friction can help maintain lower losses and better unit economics, but can hurt the company’s growth as more legitimate users will drop off during the onboarding process.

Friction is a key part of effective fraud fighting

Friction is a general term from the world of Product Management. Usually, it is attributed to anything that could cause customers to not complete their onboarding or transaction.

Some examples of what could be considered friction:

- Requiring a phone number as part of onboarding, or as part of the transaction

- Requiring customers to log in before transacting

- Requiring Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) when users log in from a new device

- Placing a transaction on a temporary hold until the customer verifies it is a legitimate purchase with accurate shipping details

- Declining a transaction due to various concerns

- Suspending the card due to various concerns

Fraud fighting teams use friction to both establish trust (confirm who is performing the purchase and that it is intentional) and to drive fraudsters away (creating product roadblocks they can not bypass). Often the goal is to look for friction options that would be relatively painless for a legitimate user, but anywhere from hard to impossible for a bad actor to complete.

One of the first strategic choices fintechs should consider is how much friction they’d like to apply and where to apply it in order to create that Goldilocks “just-right” balance.

Investing in fraud fighting pays off

Because of this balance, it can sometimes be challenging to quantify the benefits of investing in fraud fighting. But there is a link between fraud prevention investment and reduced costs when fraud inevitably happens.

Companies with a dedicated fraud program spend 42% less on response and 17% less on remediation costs than those companies with no programs in place.

Fraud Fighting: Amusement park vs. shopping mall

If you find yourself stumped about how to go about this, consider this question: Are you building an amusement park or a shopping mall?

The fundamental difference between the two is where the friction occurs.

Amusement Park

A classic amusement park has a gate at the entrance, whereby a patron pays for access. Once granted access, they can go on any of the rides or see any of the attractions they might want, typically without any further checks.

With an amusement park, friction comes up-front, similar to having an extensive onboarding process upon sign-up or login. Once a user clears that initial check (and establishes that initial trust level), the high level of trust established is used to meaningfully reduce future friction and interruption to the customer’s activity.

This results in a lower number of customers able to make it through the door, but for those who do, the experience after signing up is much smoother, and the value of each customer to the business tends to be very high.

Shopping Mall

A shopping mall is different. Usually, they welcome anyone in with open doors, yet individual stores have mechanisms and barriers to ensure folks pay (e.g., theft detection systems, cash registers, security guards).

Shopping malls have very low barriers to entry if any. Think of it as just an email and name upon initial product sign-up. But they also have incremental barriers at different points along the course journey.

Since there hasn’t been sufficient trust built “at the door” and there are no barriers to entry, attempts to control the level of fraud (in part using friction) are done at various instances throughout the experience.

This results in a much higher number of customers, but a more bumpy experience for those customers. The value of each customer to the business also tends to be smaller, though in the aggregate that can yield a meaningful net positive.

There is no “one size fits all” approach

Either approach (or a combination) can make sense for a particular product. There is no right or wrong answer. Discussing and having alignment on the approach can help ensure a consistent customer experience and adequate controls to manage fraud.

The way a company decides to approach and manage fraud is typically impacted by their risk tolerance, nature of the business, customer base, attractiveness of their product to fraudsters, the stage of their product build, financial wherewithal, etc.

Companies at any stage should think about and align internally on their approach to fraud, and should repeat this exercise periodically.